ReelBob: ‘At Eternity’s Gate’ ★★★

By Bob Bloom

“At Eternity’s Gate” is not so much about the life of Vincent van Gogh, as it is an exploration of his mind, how he saw the world and what he believed his art was supposed to accomplish.

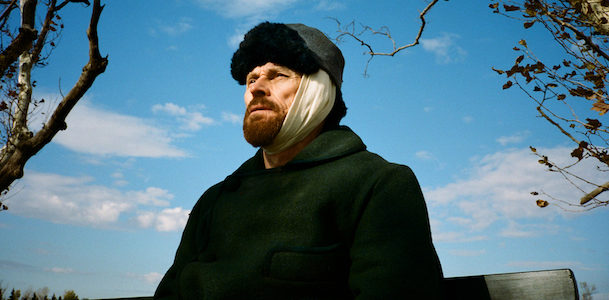

The movie, directed by Julian Schnabel, is anchored by the fierce and driven performance of Willem Dafoe, as van Gogh.

Seeing the world through van Gogh’s eyes makes “At Eternity’s Gate” compelling viewing. At times, colors jump out at you, while other sequences are muted and bleak.

The film offers some philosophical discussions about painting and the role of the artist. Van Gogh believes it’s his responsibility to show people what his eyes see — no matter how frightening or disturbing that may be.

His greatest achievement — which came to fruition after his death — was sharing with people how he saw nature: the flowers, the trees and their roots, as well as the everyday people around him — the postman and the barmaid.

Van Gogh admits that when he paints, he needs to be out of control. His is not a carefully thought-out process; he spontaneously captures what he sees.

“The faster I paint, the better I feel,” he tells his friend and fellow artist Paul Gauguin (Oscar Isaac).

Their debates about paintings and their meanings are enlightening and capture their differing views about art.

Schnabel shoots the majority of the film from van Gogh’s turbulent perspective, thus giving us a more intimate portrait of this troubled individual.

He is ably abetted by cinematographer Benoit Delhomme, who uses his lenses and filters, allowing us to see what van Gogh sees.

As with most movies about famous artists, Schnabel presents a man, battling inner demons, who walks a very thin tightrope between genius and madness.

Wisely, the movie avoids sensationalism, shunning the now-cliched scene of van Gogh cutting off his ear. Smartly, that occurs offscreen.

Dafoe’s portrayal captures the driven nature of van Gogh. He craves understanding and recognition of his work. Like all artists, he needs validation.

The eyes of his van Gogh are always searching, exploring for the perfect site or face that he can capture and show to the world.

He also is quick to display van Gogh’s manic tendencies — losing his temper or patience, for example — when prospective subjects are uncooperative or reject his requests to capture them on canvas.

Dafoe shows us the tortured soul that propels the divine spark that ignites van Gogh.

He also shows the artist’s caring and compassion, especially for his brother, Theo.

His complex relationship with Gauguin, whose approach is the polar opposite of his friend, is touching. It is an-almost brotherly interaction, as they debate and discuss their methods and views about artistic responsibility, when they lived and worked together in Arles, France, for a few months.

The film, at times, is rather jerky and slow, pausing for a few scenes of utter blackness, in which van Gogh talks about himself and his art.

“At Eternity’s Gate” is a masterful and poetic experience that may offer some insights into van Gogh that you may never have realized about this artist who, like so many, were not recognized until after they had left us.

I am a founding member of the Indiana Film Journalists Association. My reviews appear at ReelBob (reelbob.com) and Rottentomatoes (www.rottentomatoes.com). I also review Blu-rays and DVDs. I can be reached by email at bobbloomjc@gmail.com or on Twitter @ReelBobBloom. Links to my reviews can be found on Facebook, Twitter, Google+ and LinkedIn.

AT ETERNITY’S GATE

3 stars out of 4

(R), thematic elements